To discuss the issue adequately, we need to track back to the end of World War II. Between the adoption of the M1911 and the end of the war, nearly three million M1911/M1911A1 pistols had been purchased. In addition, there had been a variety of substitute standard handguns such as the Colt Commando and Smith & Wesson Victory Model, as well as leftovers from World War I such as the Colt and the Smith & Wesson M1917. There were also specialty pistols like the General Officers Pistol, better known as the Colt M1903 Pocket Hammerless.

During the progress of the war, there were a variety of foreign developments. Our British and Canadian allies had issued the Browning High-Power pistol. Our German opponents had issued a large number of double-action semi-automatic pistols ranging from pocket pistols like the Sauer 38H, Mauser HSc, and Walther PP and PPK, as well as the full size Walther P38.

In 1946, the US Army Infantry Board had been tasked with determining whether or not a new service pistol was needed and what features it should have. At the time, they decided that the M1911 pistol was in fact adequate as was the 45 Auto cartridge. While they could see the utility of the double action feature, they did not believe that this alone would be enough to justify the immediate adoption of a new service pistol. However, any future service pistol should incorporate the double action feature, and ideally, would also include a feature that would allow the slide to be racked by the trigger. However, they emphasized that the new pistol should be chambered in .45 Auto and could remain the same size as the M1911.

Yet, not everyone was thrilled with the M1911. The general complaints about the pistol were that it was too heavy and large; it recoiled too much; it was not accurate; it was not reliable; and it was not safe. A certain amount of the criticism can be blamed on the inadequate training of wartime troops, combined with a certain amount of revolver bias amongst civilian marksmanship enthusiasts.

The average soldier issued the pistol was not issued it as their primary weapon, even when it was their only firearm. They were either leading other troops, manning a crew served weapon, or assigned as a member of a vehicle crew. One could argue that the US Army had already perceived that their pistol training was inadequate before the war even began given the creation and adoption of the M1 Carbine. However, even a carbine could be too bulky for armored vehicle and aircraft crews.

The first effort to adopt a double-action 9mm pistol was sponsored by the US Army Air Forces in 1947, just prior to being granted their status as an independent branch. Even with the creation of the US Air Force, the service still depended upon the Army for the development of its small arms and aircraft guns for many years. The original characteristics were quite strict with the weight not to exceed 25 ounces, and the overall length not to exceed 7 inches. The magazine capacity was to be between 7 and 10 rounds.

While they quickly dismissed the notion of trigger-based slide racking, they oddly insisted that the new pistol be blowback-operated as opposed to using a locked breech. Interestingly enough, the original efforts at a new 9x19mm cartridge involved the use of the 158 grain full metal jacket projectile from the service .38 Special cartridge. This was intended to give a velocity of 850 fps. Contracts for development of the new pistol were ultimately awarded to High Standard and Colt.

By 1950, the specifications were slightly relaxed. The pistol could now weigh up to 29 ounces, with an overall length of 7-1/2 inches. However, the pistol should now hold at least 13 rounds like the Browning High-Power pistol. Yet, they continued to insist that the design be a straight blowback. Earlier, there had been experiments with the use of an annular chamber ring in order to delay the extraction of the cartridge, and reduce recoil.

In the meantime, Colt had been submitting more conventional alternatives, which included aluminum-framed variants of the Government Model and what was to become the Commander Model. While they were not under contract, Smith & Wesson also began development of its own lightweight, double-action 9mm pistol, which ultimately became the Model 39.

The Infantry Board started a new set of trials in 1952 to evaluate off-the-shelf revolvers and semi-auto pistols ranging from .32 to .45 Auto. Their report of April 1953 recommended that the M1911 and the .45 Auto cartridge be replaced on a one-to-one basis with a 9x19mm semi-auto. The evaluators claimed the M1911 and its cartridge were no longer suitable for Army issue in part due to their weight.

Springfield Armory drafted a solicitation for a commercial 9mm pistol competition in June 1955. However, less than a month later, the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics killed the 9x19mm pistol procurement program outright, claiming that they had plenty of M1911 pistols in inventory and that pistols were not terribly important anyway.

A few years earlier, the Air Force had already tired of waiting on the Army’s 9mm pistol development, and adopted lightweight .38 Special revolvers as the M13 Aircrew Revolver. The trick with the M13 was that both the frame and the cylinder were made from aluminum.

The U.S. Navy also considered adoption of the M13 Aircrew Revolver for its own naval aviation crews to replace their older S&W Victory Models. However, they were not as optimistic about the durability of the aluminum cylinder. This ultimately proved to be correct. A lower pressure .38 Special load was standardized as M41 Ball. It used the 130 grain projectile from .38 Super ammunition loaded at approximately 850 fps.

In 1959, the Air Force ultimately decided to scrap its stock of M13 Aircrew Revolvers. These were replaced by the S&W Model 15 Combat Masterpiece with 4” barrels. A variant of the 2” snubnose Model 15 was also standardized as the M56.

As the war in Vietnam heated up, both the Air Force and the Navy made small purchases of the Smith & Wesson Model 39. In the case of the Air Force, the pistol was issued as a General Officers Pistol. The Navy was primarily issuing it as an aircrew pistol, although it filtered out to other units. A variant of the Model 39 modified for use with a sound-suppressor, known as the Mark 22, was also developed for the Navy SEAL teams.

By the late 1960s, the Army also started to see a need for a new General Officers Pistol to replace the long discontinued Colt Pocket Hammerless. Among the pistols tested were the Smith & Wesson Model 39, the Walther P38, a 9x19mm precursor to the commercial Colt Combat Commander known as the M1969, and an in-house compact conversion of the M1911 from Rock Island Arsenal. The latter was ultimately adopted as the M15 General Officers Pistol.

By the early 1970s, the Air Force began to become disillusioned with the performance of the M41 Ball. Experiments were made to improve the performance of the cartridge, including short case variants, as well as deep-seated variants. The latter option was ultimately standardized as the PGU-12/B. The Air Force also started to look at the potential of modifying the Model 15 revolver to fire the 9x19mm cartridge.

In August 1977, the Air Force Armament Laboratory contacted manufacturers inviting submission of 9x19mm semiautomatic pistols. The basic goal was to keep the selection process simple. The military wanted to select a commercial, off-the-shelf “non-developmental item” (NDI) that would replace all existing handguns in the Department of Defense (DOD) inventory, and thus avoid conducting a research and development program.

The pistols should be capable of single and double-action fire; have a magazine capacity of at least 13 rounds; the magazine catch should be easily accessible and drop the magazine free upon release; the slide should lock to the rear when empty; the ambidextrous safety must lower the hammer without touching the trigger and lock the firing pin when engaged; the magazines should be equipped with a removable floor plate; and the pistols parts should be interchangeable.

The submissions included the Beretta 92S-1; the Colt SSP; the FN GP35, ‘‘Fast Action’ Hi-Power, and Double Action Hi-Power; the HK P9S and VP70; the Smith & Wesson 459A; and the Star Model 28. The HK entries and the basic FN GP35 were quickly dismissed due to failure to meet the basic technical requirements. Ten each of the remaining candidates were purchased for testing. An equal number of issue M1911A1 pistols and S&W Model 15 revolvers were used as control samples.

The test pistols were to be capable of functioning under adverse operating conditions, including dust, mud, heat, and cold. Only eight significant malfunctions were to be allowed during the 5,000-round endurance test. No candidate passed the tests, but the Beretta was considered to have performed the best of all of the handguns tested, including the control models. Critics seized upon the poor performance of the control M1911A1 pistols to suggest that the Air Force tests were unscientific and flawed. This ultimately set the stage for the Army to take over any future pistol trials.

In 1978, the DOD Material Specifications and Standards Office initiated two joint service studies to investigate the benefits of standardizing handguns. The first study investigated the possibilities of reducing the types and inventory of handguns. It recommended a reduction from 101 to 31 federal stock numbers of ammunition available for procurement. DOD followed through on the recommendations in FY 1980.

The second study investigated whether or not a commercially available handgun, which could use the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) standard 9mm cartridge, could be adopted as a substitute for any or all of the .38 and .45 caliber handguns in the inventory. The study further investigated which models of the handguns in the inventory could be eliminated if no substitute could be found.

The US Congress had already begun to take interest in the testing, and seemed particularly peeved concerning the number of different handguns being issued by the different services. The Joint Services Small Arms Program (JSSAP) was established in 1979, and one of their first tasks was sorting out the pistol issue.

The DOD made the Army responsible for this second study because it was the “executive agent” for small arms. The task fell to the JSSAP committee which reported its findings in June 1980. The study concluded that a 9mm handgun capable of firing the NATO standard 9x19mm Parabellum ball cartridge should be selected as the standard caliber handgun for the services. JSSAP recommended that a single family of 9mm pistols be adopted, with a full-size and compact model.

Subsequently, the Army submitted to the Office of the Secretary of Defense a proposed acquisition strategy which utilized a competitive procurement of a commercially available 9mm weapon. Early in 1981, the Acting Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering James Paul Wade, Jr. approved the acquisition strategy and directed the Army to prepare a schedule leading to a contract award in January 1982.

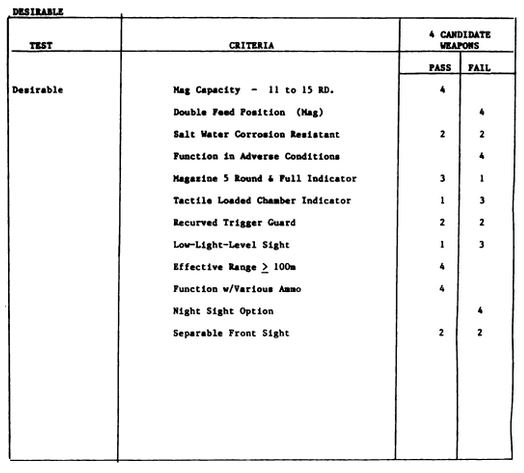

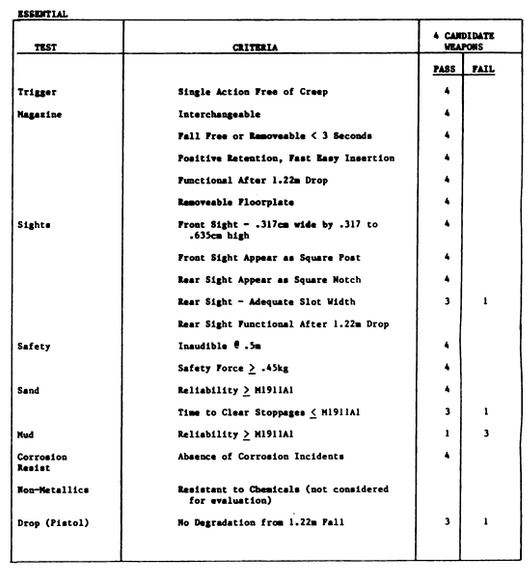

In June 1981, an updated set of joint service operational requirements (JSOR) was written by JSSAP and approved. 85 requirements were laid down for the winning pistol, of which 72 were mandatory while 13 were desirable. In September 1981, two weeks prior to the Army source selection test start, the Air Force member of the JSSAP committee objected to the original JSOR requirement of 643 mean rounds between operational mission failure (MRBOMF) as being too low.

The Air Force’s experimentation and testing had attained more than two times that figure (1,500 rounds) and consequently, the Air Force insisted on raising the JSOR requirement. The first JSOR figure was the original 1911 requirement number for the M1911A1, which according to the Army, it never met. This figure was restated in the JSOR since it was believed that in the period between 1911 and 1982 the state-of-the-art would have improved to the point where a modern handgun could meet it. Negotiations concerning these two figures (643 and 1,500) resulted in a compromise at 800 MRBOMF which was added to the JSOR as an amendment in September 1981.

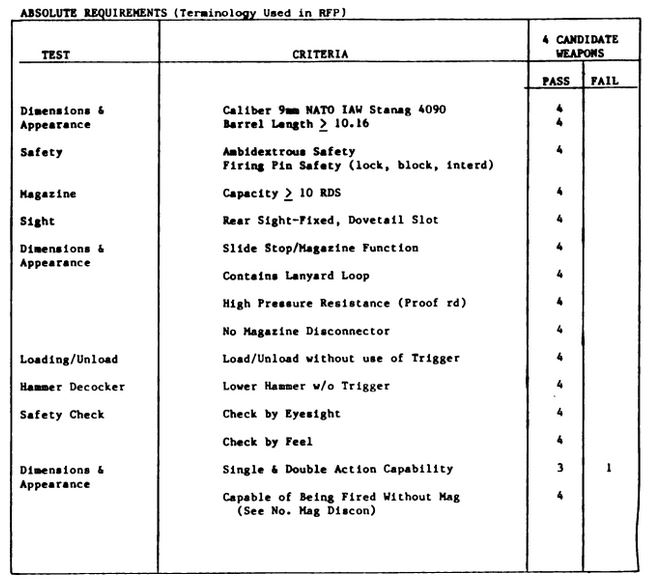

The Army Armament Materiel Readiness Command (ARRCOM) then issued a request for proposal (RFP) to industry in the United States and abroad which envisaged a five-year procurement. The RFP asked for an “off the shelf” gun which would have the following design features:

1) A double-action weapon, in which the first shot from safe gun could be fired by a pull of the trigger, without the need for manual cocking;

2) A positive “hammer drop” safety, in which the hammer would be prevented from acting on the firing pin when the safety lever would be engaged;

3) An ambidextrous safety;

4) The ability to lower the hammer and both load and clear the weapon with the safety “on “; and

5) A minimum magazine capacity of 10 rounds, so that the loaded weight with 9mm ammunition would be the same or less than a loaded .45 with its seven-round magazine.

Due to the short time between the the Request for Proposal and the required delivery of test samples, only four candidates were submitted: the Beretta 92SB (an improved 92S-1), the HK P7A10, the S&W 459M, and the SIG-Sauer P226. The Army announced on 19 February 1982 that it had rejected all the candidates. Of the four candidate weapons, Smith & Wesson had the highest evaluated score considering price, technical, and other factors. Strangely, the Beretta now finished dead last, even behind the control M1911A1.

ARRCOM immediately dissolved its source selection evaluation board but the 9mm Pistol Project Office, which was a part of the Infantry / Air Munitions Division, continued. The 9mm Pistol office continued to work on new test plans, and a new scope of work for the pistol and for test ammunition.

Congress and the Government Accounting Office (GAO) were infuriated by the waste of money for no results. The GAO’s March 1982 report on the 9mm program recommended that the DOD reexamine the need for replacing its .45 caliber pistols due to the cost of the program and its recognized low priority. Congress wrote legislation which held fiscal 1983 funds for .45 caliber ammunition and M1911A1 spare parts hostage until the US Army could formulate a test series that a manufacturer could pass. The 1983 authorization bill went further and prohibited the further evaluation and testing of a 9mm pistol. The FY 1984 authorization bill likewise provided no funds for procurement but lifted the ban on evaluation and testing.

In May 1982, the Secretary of Defense informed the House Armed Services Committee that the Army would develop new joint service requirements as well as redesign the selection and testing programs so that they would not be so stringent. The goal was to establish these programs by June 1983 and make a selection by July 1983.

In August 1982, DOD approved the new joint service operational requirement. The Army emphasized that the new tests would not be development trials but would be arranged to pick the best “off-the-shelf” gun. In September 1982, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (PDUSDRE) James Paul Wade, Jr. deleted, without prejudice, the JSOR’s reference to a smaller, more concealable weapon under the rationale that the weapon selected might also be adequate to meet concealed and aircrew requirements.

Fiscal year 1983 closed without a selection. Meanwhile, the House Committee vented its frustration over the slowness of the Army in several reports.

On 13 July 1983, the Department of Army Materiel Development & Readiness Command (DARCOM) approved a charter giving the 9mm Pistol Project Office product manager status. Ву 20 July 1983, the office completed the new request for proposal. However, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research, Development and Acquisition Percy A. Pierre indicated that he wanted the entire acquisition process speeded up. He wanted a separation of the test phase from the procurement phase of the acquisition. The 9mm Pistol Office eventually developed a plan for a concurrent request for test samples and a request for proposal which the Assistant Secretary approved on 19 August 1983.

In implementation of the plan, the Army Armament, Munitions and Chemical Command (AMCCOM) at Picatinny Arsenal began to conduct tests in conjunction with the Air Force on various commercial pistol models in effort to provide information for the Deputy Secretary of Defense. In addition, the office attempted to resolve the problem of what policy should be followed in the future to assure the availability of adequate supply of the weapons.

A major question was whether or not the guns should be maintained or “thrown away” when they no longer functioned properly. Initial attempts to analyze the throw away issue foundered due to inadequate data. The office again started to gather new data with the help of several other command organizations. Ultimately, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Thayer resolved the issue early in October 1983 when he chose the traditional Army maintenance concept for small caliber weapons. He rejected the throw away concept as too expensive. Moreover, Thayer directed all services to replace all .45 and .38 caliber handguns with a 9mm handgun.

On 26 September 1983, AMCCOM released a draft request for test samples (RFTS) to industry for the proposed 9mm pistol. At a subsequent bidders conference to discuss the RFTS, industry representatives requested additional time to prepare their weapons for the tests, so the final RFTS, issued on 9 November, called for submission of the test samples to Aberdeen Proving Ground on 31 January 1984.

The XM9 trials started again in January 1984. The competitors included the Beretta 92SB-F (an improved 92SB), the Colt SSP, the FN Double Action Hi-Power, the HK P7A13, the SIG-Sauer P226, the S&W 459M, the Steyr GB, and the Walther P88.

Each of the eight prospective contractors submitted 30 weapons for testing. Ten of each were sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground where they were numbered, checked for proper dimensions, and then subjected to a series of tests to determine their operation in a number of different environmental conditions. Ten were sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for durability trials where they were fired by hand between 3,500 and 7,000 times to determine how well they stood up under stress. The final ten of each model were sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, where representatives of all service branches tested how well the weapons could be relied upon to hit man-sized targets when fired by people of varying sizes.

During the testing, Colt and FN voluntarily withdrew, and Steyr was eliminated on technical grounds. On 18 September 1984, Heckler & Koch, Smith & Wesson, and Walther were found technically unacceptable by the Army just before price proposals were due to be submitted.

Heckler & Koch and Smith & Wesson filed bid protests with the GAO. Heckler & Koch’s protest was denied on its merits, while Smith & Wesson’s was dismissed when it chose to pursue its remedies in court. Smith & Wesson lost its case in both the Federal District Court and the First Circuit Court of Appeals. Ironically, the GAO concluded that S&W was improperly eliminated over a rounding error in the Metric-to-English units conversion in calculating the firing pin force, as well as the average rounds for the frames’ service life.

The final test reports on the 9mm candidates were received by their suspense date of 24 September 1984. In the end, only the SIG-Sauer P226 and 92SB-F were considered to have passed all of the tests.

On 14 January 1985, the Department of the Army announced that the Beretta 92SB-F would be the standard personal defense weapon for the US military, and that a five-year fixed price contract for 315,930 weapons would be awarded within 30 days. In the words of the announcement, the Beretta was one of only two candidates to satisfactorily complete a rigorous test program designed to verify both performance and durability under both normal and adverse environmental conditions. It met or exceeded all mandatory requirements and judged to have the lowest overall costs and provided potential further savings over the life of the weapon due to durability advantages.

The GAO closed its file on Smith & Wesson’s protest on 14 February 1985, and the formal contract was signed with Beretta on 10 April 1985. However, this did not tamp down on the controversy.

The XM9’s First Article Test was held at Beretta’s main plant in Gardone Val Trompia, Italy in late July 1985. In such a test, the contractor provided samples – in this case 20 pistols – of their product which prove their readiness to produce and deliver an acceptable version of what the Department of Defense ordered. Beretta failed the First Article Test.

1) Twelve parts of all 20 guns did not conform to Beretta’s drawings and specifications. These included the slide, hammer, receiver, trigger, trigger bar, safety, locking block, magazine, and grips;

2) A vital gauge used to measure proper mating of the slide, locking block, and barrel was out of tolerance with Beretta’s own specifications;

3) A number of Berettas failed to meet the firing-pin energy test; and

4) Pistols also failed the Army’s revised accuracy standards, standards that had been loosened since the XM9 trials testing.

Failure of the First Article Test could have been grounds for termination of the XM9 contract, but Beretta was allowed to continue, raising the ire of Smith & Wesson and its Congressional supporters.

SIG-Sauer also sued. After a series of bids in which SIG-Sauer started as the low bidder, Beretta had been awarded the contract in 1985 due to a lower price quoted on its spare parts. Allegations were made that Beretta was fed SIG-Sauer’s final bid in order to undercut it.

After a series of Congressional investigations, The 1987 Continuing Appropriations Act directed the Army to hold a competition during fiscal year 1987 for the follow-on procurement of the 9mm handgun in fiscal year 1988. In conducting the competition and follow-on procurement, the Army was directed to use the same performance specifications as those used in the 1984 tests.

On 30 September 1987, the Army issued a request for test samples. The request stated that the M9 would be exempted from retesting because it has continued to meet all production and acceptance requirements. This decision raised concern with officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) because they believed that the M9 along with the other competitors’ weapons should be subjected to identical tests using the new US manufactured 9mm NATO standard ammunition.

SIG-Sauer insisted that the P226 didn’t need to be retested either since it had passed XM9 as well. In response to a bid protest filed by Smith & Wesson, the GAO stated on 25 February 1988 that Smith & Wesson should not be required to be retested on those elements which it had passed in the earlier 1984 competition and testing; or if Smith & Wesson was going to be completely retested, then the M9 should also be retested. Two weeks later, on 11 March, the Army asked the GAO to reconsider their bid protest decision, and on 14 April, the GAO affirmed their original decision.

Between September 1987 and April 1988, OSD officials continued to voice their concerns about the Army’s lack of compliance with congressional direction and DOD policy. In fact, the DOD withheld $5.3 million of Army procurement funding for fiscal year 1988 in order to force compliance.

Just before the original XM10 RFTS in September 1987, the Army began experiencing quality and safety problems with the M9. The first problem was frame crack indications. The second and more serious problem was the slide assembly failures, first seen in Navy-owned Berettas.

Indications of frame cracks were first noticed during the lot production testing of M9 produced in September and October 1987. At that time the Defense Contract Administration Services representative at the Beretta plant recommended that the Army not accept the two lots totaling about 12,000 handguns. The M9 program office did not accept the recommendation because there was not clear evidence at that time that the frames in fact were cracked. Because of the frame crack problem, the Army rejected the December 1987 and January 1988 production lots also totaling about 12,000 weapons.

In February and March 1988, Beretta continued to produce 6,000 M9 a month but did not submit the lots for production testing. Thus, at the end of March there were about 24,000 M9 produced but not accepted by the Army.

An engineering change proposal to modify the manufacturing process was implemented by Beretta in April 1988. The handguns manufactured during December 1987 and January 1988, as well as those manufactured in February and March, were subsequently reworked, tested, and accepted by the Army. The 6,000 M9 manufactured in April 1988 were submitted to the Government for testing and acceptance in late August.

Army officials stated that they plan to stop accepting delivery of M9 after the April 1988 lot was tested until the slide problem was resolved. At the time, they estimated that acceptance of M9 could resume some time in January 1989.

About 3 weeks after the Army’s first M9 slide failure occurred on 8 February 1988, the Army issued a safety message to all M9 users. Army officials stated that they had not responded to the two earlier slide failures on Navy weapons because of the uncertainties about the type of ammunition used in the weapons, specifically the use of non-NATO spec subsonic loads. The 1 March 1988 safety message advised all military M9 users of the slide problem, and instructed the users to maintain a count of the number of rounds fired and to replace the slides about every 3,000 rounds.

The initial set of XM10 testing was ultimately cancelled, even though FN, Ruger, S&W, and Tanfoglio intended to submit samples. After discussions between the House Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, the Army, and OSD, the Army announced that the ongoing competition for follow-on procurement of the 9mm handguns was being canceled and that a new competition including testing of the M9 handgun would be conducted. The Army’s decision, which appeared in the 28 April 1988 issue of Commerce Business Daily (CBD), advised that a request for test samples would be issued on 10 May 1988, and a draft request for proposal 10 days later.

The XM10 tests were finally rescheduled for August 1988. Since Beretta refused to submit samples, the Army used off-the-shelf M9. Beretta protested this, but since they had already refused samples, this protest was rejected. SIG-Sauer also refused to submit samples, standing on principle that they had passed XM9 the first time. S&W submitted their 459M yet again, and Ruger submitted their new P85.

In the meantime, the M9 slide breakage epidemic largely resolved itself once slide production was moved from Italy to the US. The MWO 9-1005-317-30-1 retrofitting of the large head hammer pin to the 92FS standard began in March 1989.

The Pentagon announced on 24 May 1989 that the Beretta M9 had also won the XM10 trials. Once again, there were allegations of impropriety. The Army refused to relax their requirement for a chromed bore, even if the barrel was made from stainless steel. Moreover, the S&W failed tests that they had passed in XM9. They were the only pistols to pass the XM9 accuracy requirements, but failed the XM10. The S&W also failed the corrosion tests in spite of the fact that the affected parts which failed XM10 were made from stainless steel while the same parts in the successful XM9 samples were made from carbon steel. Ruger wasn’t provided any reason why their samples failed.